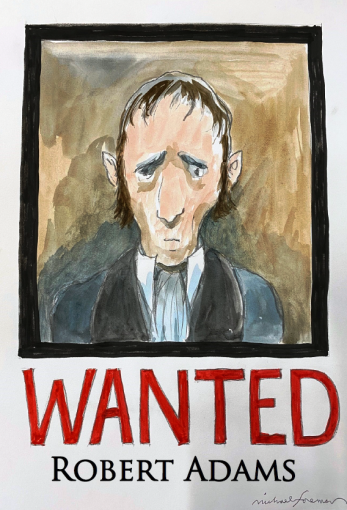

Robert Adams

Robert Adams served in the Royal Horse Guards—known as ‘The Blues’—during the French Revolutionary Wars. He left service in about 1801, just before the Napoleonic Wars began in 1803. Adams was a cordwainer—a posh bootmaker—by profession. Cordwainers were highly skilled workers who used only new leather in their craft, thus making their product more expensive. In contrast, cobblers made more inexpensive shoes using reused leather. Cordwainers were one of the many professions with established guilds or companies that provided economic and social networks for their members. Guilds like the City of London’s Cordwainer Company protected their wages by ensuring tradesmen had to undertake a seven-year apprenticeship mandated by the Elizabethan Artificers Act of 1563. In 1812, the government repealed the Artificers Act so that cheaper labour could be secured during the Napoleonic Wars. This threatened the livelihoods of skilled tradesmen, like many of the Cato Street conspirators.

With the onset of the Napoleonic Wars in 1803, the number of tradesmen working with leather increased as British army officers were required high-quality leather boots. Adams followed the regiment to Cambrai, France, where they were stationed on garrison duty at the end of the Napoleonic Wars. Cambrai was a major British military stronghold where Adams would have had plenty of work as a cordwainer. There he reunited with John Thomas Brunt, a fellow cordwainer, who Adams knew during his time as a soldier. It has been speculated that Brunt left Cambrai soon after business quarrels with Adams.

Adams likely lost his livelihood as a cordwainer when the occupational troops returned to Britain and demobilized the Royal Horse Guards regiment. In 1819, Brunt and Adams met again in London as neighbours living at Hole in the Wall Passage. A year later, Brunt introduced Adams to London radical and Cato Street Conspiracy mastermind Arthur Thistlewood. Adams attended regular meetings with Thistlewood before and after serving a stint in Whitecross Street debtors’ prison during January 1820. If scrapes with debt didn’t radicalize Adams, the debauchery of the Prince Regent and the madness of King George III that the ex-soldier witnessed during his service in the Royal Horse Guards may have been enough to drive Adams to act.

Thistlewood was impressed by Adams’ military experience and abilities—Adams was a skilled user of the 1794 patent cavalry sword— and chose Adams and John Harrison to lead an attack against members of the Prime Minister’s Cabinet while they dined at Lord Harrowby’s home. Just before the attack was set to begin, the Bow Street Runners ambushed the conspirators and Adams, along with Arthur Thistlewood, William Davidson, John Thomas Brunt and John Harrison, fled the scene, evading capture by climbing through the window and over the roof of the Cato Street cowshed.

Several days later, Adams was arrested and charged with High Treason. He decided to make a deal with the Home Secretary, Lord Sidmouth. Adams agreed to be a main witness for the Crown and government at the trials of the charged conspirators. Conspirator John Monument also made a deal with Lord Sidmouth and served as a witness, giving evidence against the five conspirators who pled not guilty: Thistlewood, Davidson, Ings, Tidd and Brunt. The version of events Adams presented in the trials revealed he was coached by the Privy Council and learned a scripted version of events by memory. For divulging all he knew, the charge of High Treason against Adams was dropped.

Though Adams escaped the fate of his fellow conspirators—public execution or transportation for life—he did not evade the law for long. Adams returned to debtor’s prison shortly after five of the convicted conspirators were executed on 1 May 1820.

No Comments

Add a comment about this page