The Cato Street Conspiracy: A Real Life Drama set like Bridgerton in Grosvenor Square Part One

We began the process of bringing the story of the Cato Street Conspiracy to a wider audience in Cato Street itself with a festival to mark the bicentenary of the uncovering of the plot on Sunday, 23rd February 2020. Little did we know that we were perched on the precipice of the Covid 19 epidemic. Many of our plans had to be abandoned, postponed, or drastically altered, but one year on from that festival a consequence of lockdown has given us an opportunity to reach out with our story to a new audience.

The Lockdown Phenomenon set in Grosvenor Square

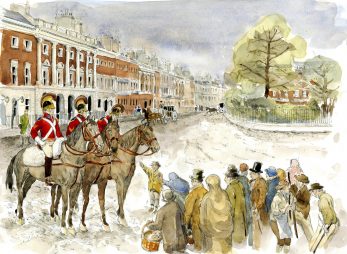

On Christmas Day 2020, Netflix released its Regency romance adaptation “Bridgerton.” By a lucky coincidence the biggest tv phenomenon of lockdown had set itself in the same era, in the same place, that the Cato Street Conspirators had targeted in 1820. Bridgerton is not normally something that I would watch. However, with little else to do other than gorge on television and Quality Street, I sat down for the first episode with my wife and daughters. We were just one of 82 million households who saw the credits role with a panoramic swoop across Regency London to a place I knew very well. I had spent the previous six months providing images of Bridgerton’s Grosvenor Square setting to our project artist Kate Morton and our 3D VR visualisers RH Viz, so like Bridgerton, that they could bring alive that very same location alive for a 21st century audience. https://rhviz.com/portfolio/westminster-archives-grosvenor-square/

A Reimagined Regency London

Bridgerton depicts Regency high society for that 21st-century audience through brightly dressed couples dancing to string quartet versions of hits by Ariana Grande and Shawn Mendes. The series is based on the novels of American novelist Julia Quinn, and was brought to the screen by American producer Shonda Rimes. One thing that makes it stand out, is a diverse casting not normally associated with Regency dramas. The Prince Regent is nowhere in sight in Bridgerton’s London; instead, Golda Rosheuvel as Queen Charlotte, wife of George III, presides over London society, in a casting choice that hints at evidence she may have had Black ancestry. The aristocracy itself is likewise peppered with Black men like the Duke of Hastings played by Rege-Jean Page, who have been elevated to their positions by the benevolent king, whose madness renders their social status precarious. The reasoning behind Bridgerton’s diversity has been explained by Dr. Hannah Greig, the historical advisor to the series:

“the past is more diverse than we tend to see on screen, and we tend to accept in our popular imagination. But it’s also a fictionalising, asking what history might look like under certain different circumstances.”

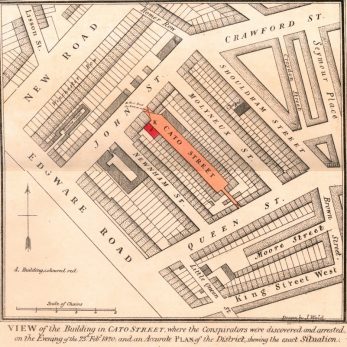

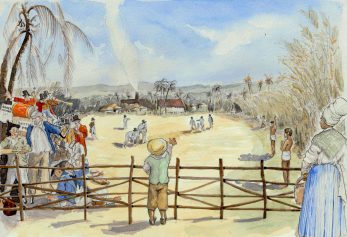

We know from the story of the Cato Street Conspiracy that early 19th-century London was much more diverse than many previously believed. The conspirators were drawn from the ranks of the Spencean Philanthropists, who sought to overthrow the Regency elite. One of their number, who only missed taking part in the plot because he had been imprisoned for seditious libel was the Jamaican Robert Wedderburn. Before his imprisonment, he had regularly met with the conspirators at the Marylebone Union Reading Rooms, at 54, Queen Street, (now Harrowby Street) close to Edgware Road. Wedderburn was radicalised by childhood memories of his enslaved grandmother being beaten in front of him. He had seen similar brutality whilst serving in the Royal Navy before coming to London, aged 17. Here, he lived amongst the “London Blackbirds”, in the notorious St. Giles Rookery (modern day New Oxford Street). This was a strong community of former slaves, and sailors, who despite their poverty, found freedom in London as slavery had not been acceptable since Lord Chief Justice Mansfield, had ruled in 1767 that, as soon as a slave set foot on English soil, he became free.

The Bon Ton Built on Slavery

Bridgerton is based around the formalised courting season in 1813 London, as the ‘Bon Ton’, (the fashionable social elite) scheme to pair off their young offspring. This ritual, was known as the marriage mart, as the upper 10,000 people in Regency society, “The Ton” came to London for parties, balls, teas, and promenades all with the purpose of finding the “right match.” The main storyline follows the relationship of Daphne Bridgerton and the dapper Duke of Hastings, Simon Basset, who agree to a fake a courtship as a means of avoiding this marriage cattle market. Bridgerton uses leading characters like the Duke of Hastings in roles that people might not expect to see Black people, such as the aristocracy. The racial integration of the nobility moves away from pure historical fact and forms part of the fantasy world of Bridgerton. Midway through the series it is explained that when King George III married the mixed-race Queen Charlotte he had granted peerages in her honour to a number of Black people, including Simon’s father, the Duke of Hastings. Bridgerton poses the question of what society might have looked like under certain different circumstances

As soon as I saw the Duke of Hastings played by Rege-Jean Paul, I thought of conspirator William Davidson, a mixed-race ‘Jamaican born in its capital city, Kingston, in 1786. William was the second son of a white Scottish father and free black mother, whose ancestors had been African slaves producing the sugar and rum that fuelled Jamaica’s slave economy. The physical similarities between Davidson and Bridgerton’s Duke of Hastings may be there, but not the links to slavery. One glaring omission with Bridgerton is the way in which it evades the question of how ‘the Ton’ attained the wealth it displays so conspicuously on screen. During the Regency era, most of the real-life Ton acquired their wealth through direct or indirect involvement in slavery or colonialism. The landowning elite exported cotton, sugar, coffee, wood, and metals from their overseas properties, or were involved in firms manufacturing consumer goods out of those raw materials. Although Bridgerton is set after Britain banned the international slave trade in 1807, much of the British aristocracy still made money from slavery. It was not until the Slavery Abolition Act (1833) that slavery was completely abolished within the British Empire.

No Comments

Add a comment about this page