Revolution & Paine

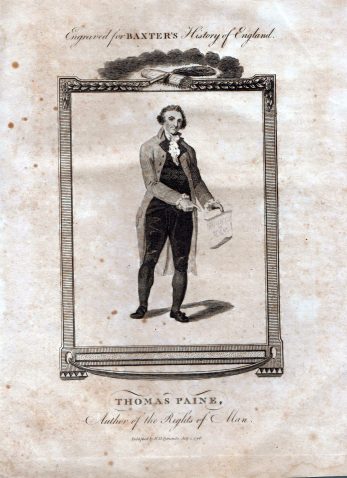

Revolutions do not happen in a vacuum. That is to say, the preceding events before a revolution are essential in understanding why a population would go so far as to overthrow their former mode of government, and establish a new order. This includes other revolutions and the ideas they spawn, not just events within a nation or in close geographic proximity. In this sense, the Cato Street Conspirators can trace the lineage of their revolutionary thought to the two greatest Revolutions of the 18th century and one of the most important works that helped shape them – The American and French Revolutions, as well as Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, Rights of Man, and The Age of Reason.

The American Revolution

As a former British Colony, the American Revolution would still be on the collective consciousness of English Radicals in the early 19th century. The independence of America, and the formation of a Democratic system of government in the former colony was a shock to the world at the time. In fact, the American Revolution was one of the first of a revolutionary wave known as the Atlantic Revolutions – from the 1760’s to 1870’s numerous European nation states underwent some form of Revolution, such as the Batavian Revolution in 1795, the Irish Rebellion in 1798, and the Kościuszko Uprising in 1794. Additionally, it also marks the beginning of the Decolonization of the America’s, with examples such as the Haitian Revolution in 1791, the Venezuelan War of Independence beginning in 1810, and leagues more. All of this goes to say that Revolution was no longer the unthinkable concept that it was in the early-mid 18th century. It is certain that the success of these revolutions against the traditional powers of Europe invigorated the conspirators and gave them the impetus to hatch their own audacious plots.

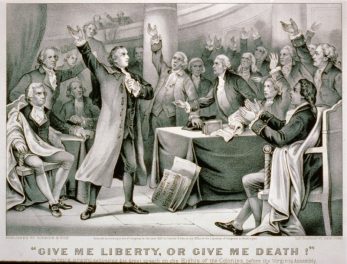

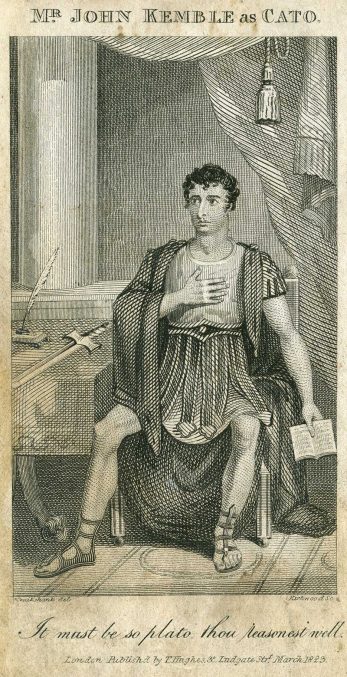

A connection between the American Revolution and the Cato Street can be seen in the works of Thomas Paine, and his work Common Sense. In this pamphlet, Paine advocates for the Thirteen Colonies to declare independence from Great Britain and establish a Republic. It was widely successful in the Colonies, and in a very real sense made the American Revolution possible. As American founding father and future president of the United States John Adams was reported to have said, in regards to Common Sense that “Without the pen of [Paine], the sword of Washington would have been wielded in vain.[1]” The work was estimated to have sold 100,000 in 1776 alone, a massive success. While Common Sense primarily was written with the intention of promoting an American Revolution, it also found a home in Europe, specifically France and Britain for its broader sections. These included criticism of the English constitution, and rejection of divine right rule through the citation of scripture. These sentiments rapidly found a home in English Radical circles, in particular none other than Thomas Spence. While there were certainty spots of conflict between the two thinkers, in particular their view on private property, both subscribed to ideas regarding an expansion of suffrage to include those traditionally left out of the civic process. The Conspirators read Paine’s work at the Maryebone Union reading room after it was banned by the British government following the Peterloo Massacre. There is little doubt that Paine’s ideas, as well as the ideas of the American revolution were involved in making the Cato Street conspiracy possible – clear evidence can be seen in Ing’s last words which was a rallying cry of American Revolutionaries – “Give me death or liberty”. The phrase was made popular at the time by the American politician Patrick Henry, and his passionate speech is often credited with the decision by Virginian legislators to formally deliver troops to the Revolutionary side. Interestingly enough, a similar phrase can be traced back to the first few years of the 18th century, with the 1713 play Cato, a Tragedy, which was immensely popular in the colonies. The play follows the stoic but doomed resistance of Cato the Younger against Julius Caesar’s totalitarianism. Henry’s quote is believed to be referencing the line “It is not now time to talk of aught/But chains or conquest, liberty or death” from act II, scene 4. Numerous other references can be found throughout the history of the American Revolution to the play – another example can be seen in Nathan Hale’s final words, “I regret that I have but one life to lose for my country,” which is supposedly a reference to the play’s act IV, scene 4, “What a pity it is/That we can die but once to serve our country.” As a result of this play, Cato was seen as a virtuous figure of justice and liberty in the face of tyranny – it is no wonder why ideas espoused by the play made their way into revolutionary action. Like the Americans, as well as the ancient Romans, the Cato Street Conspirators saw themselves as a longstanding tradition of righteous men standing against dictatorial tyranny.

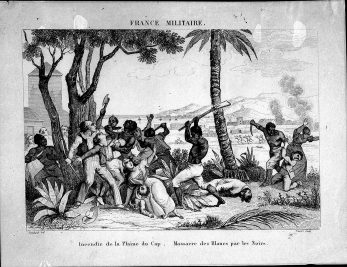

The French Revolution

Even greater than the impact of the American Revolution was that of the French Revolution. France throughout its history had been a bastion of absolutist authority for the majority of what is considered the early modern era, starting in 1500. To have such a powerful and traditional nation succumb to Revolution was unthinkable to the majority of Europe, and the atrocities that followed shaded the policies of European nations for the years to come. In a very real sense, the increasingly reactionary English government that Thistlewood and his conspirators took issue with was a response to the horrors of the Reign of Terror and the subsequent Napoleonic Wars. Such tumultuous events did not only shape the reaction of governments, but also the people controlled by them. The American Revolution was an impressive feat to be sure, but it was also based thousands of miles away from the mother nation. Supplies, men, and information took months to go from Britain to the Colonies, and vice versa. Additionally, the colonies needed financial and military assistance from a suite of nations (France, Spain, the Dutch Republic). The French Revolution on the other hand showed that the traditional structures of power could be challenged not only by an external force, but by the people themselves – and that the people could win. Such sentiments gave the conspirators the morale to plan to execute such an audacious plan, and influenced them in other ways. Thistlewood himself claimed to have taken part and served as a captain with the French Grenadiers at the height of the Revolution! Speculation followed his rise to prominence in the public eye, with contemporary writers asserting his claim as fact, some asserting that he was in Paris at the height of the Terror, and fought for the French at Zurich in 1799. These claims are disputed, and there is good reason to suspect that it is fabricated. Thistlewood arrived shortly after the overthrow of Robespierre in Paris, so the claim he was in Paris at the height of the terror is unambiguously false. In terms of his military service, it does not seem likely that an Englishman, who’s country was at war with France at the time, could rise to the rank of Captain in new army of the French Republic. Likewise, despite claiming to be present at the battle of Zurich, he did not know the name of the French commander he was supposedly serving under. Just a year after returning from France following the Treaty of Amiens, Thistlewood was commissioned as an officer in a Royal Militia in 1803; something unlikely for a man who proclaimed himself to have “became initiated in all the doctrines and sentiments of the French Revolutionists,” and to have actually fought for such ideals just a year earlier. Additionally, Thistlewood was only considered to be a subject of scrutiny by the British government after 1814, which is incredibly unlikely if his earlier stories about serving in the French Grenadiers was not a fabrication. It is believed that these claims stem from Thistlewood’s move to London in 1810-11, and his newfound association with radicals like Thomas Spence. Such stories would lend him credibility as a fervent revolutionary, and help build an aura around his figure within these circles.

Thomas Paine took it upon himself to defend the French Revolution from popular critiques, particularly against Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France. In the Rights of Man, Paine emphasizes that a government that does not defend the rights of its people can be legitimately overthrown by popular political revolution. He divides his book into several sections, disparaging aristocracy and hereditary rule in one, proposing practical reform of the English government in a more Democratic sense in another, and advocating welfare for the poor in a third. Such ideas fit nicely into the Spencean framework of Thistelwood and his conspirators.

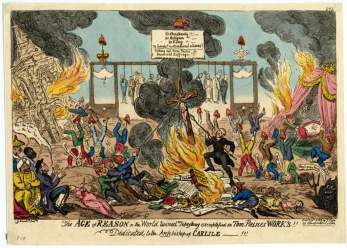

The Age of Reason

Lastly in regard to Thomas Paine comes his work The Age of Reason. In this Paine argues on behalf of Deism, a religious position that rejected the revelations that Christianity was built on and instead emphasized the “free rational inquiry” of all people and asserts that enlightenment values like reason and observation are the basis for religious knowledge, in establishing the existence of a Deity. The book was highly received in the United States, but not so much in Britain. It called for religious freedom as well as the abolition of the clergy as they were seen to effectively enslave those under them – as a result, Deists as a result saw themselves as intellectual liberators. The Age of Reason’s influence can be seen in the trial of the conspirators, with William Davidson having reportedly “changed his religion in consequence of reading Paine’s Age of Reason” which he had received thanks to Richard Tidd. Additionally, Robert Adams testimony was doubted thanks to his renunciation of Christianity after “reading that infernal work, Paine’s ‘Age of Reason.’” Following the death sentences of Thistlewood, Ings, Tidd, Davidson and Brunt, the Newgate Prison Vicar came up against the deism of the conspirators. None would pray with him at first because of their beliefs – only Davidson would relent and make use of the Reverend Dr. Cotton. Davidson spent his last moments deep in prayer, holding the reverend’s hand as he was marched to the execution site. His last words were, “Lord God I pray for the prosperity of King George IV,” a definitive refutation of his earlier deist beliefs.

The Cato Street Conspiracy was a highly ambitious plot that was born out of the surrounding historical events and influential works. Of particular importance were the American and French Revolutions, as well as the works of the Revolutionary Thomas Paine.

No Comments

Add a comment about this page