How did Prime Minister Spencer Perceval push Britain to the point of Revolution?

Angry Artisans Before the Cato Street Conspiracy

The Cato Street Conspiracy was the explosive and desperate culmination of years of injustice and pushed to action by the threats towards the livelihoods of artisans and skilled labourers in England. By plotting to kill the Prime Minister and his Cabinet, the Cato Street conspirators accepted that, if they were caught, the consequence was death by being hung, drawn and quartered. This mission for justice was not taken on lightly. What drove these men to risk everything? Why did they feel assassination was their best option for change?

The Orders in Council: 1807

What we have to understand is that the Cato Street Conspiracy was something that fermented over a long period of time. Key to the anger and resentment that drove the conspirators was the impact that the Napoleonic Wars had on Britain. They may have resulted in triumph on the fields of Waterloo, but they created hunger and unemployment in the people of this country. People felt angry at an unaccountable government of landowners who were able to make decisions that impacted on ordinary people. One key politician who drew the ire of the masses was Spencer Perceval. He was Chancellor when the 1807, Orders in Council were passed. This act of parliament aimed to blockade trade to Napoleon’s Europe to bring about economic pressure that would end the war. The Orders allowed the Royal Navy to board and seize the goods of any ship believed to be transporting goods for France or its allies. William Davidson was most likely involved in this practice as a sailor in the Royal Navy and would have seen the damage the navy’s actions were causing when he returned home to England.

The Orders worked so well that they destroyed global trade and brought about economic misery at home. Perceval came under great pressure to repeal the acts, particularly from the Northern cotton barons and their American allies. However, once Perceval became Prime minister in 1809 he steadfastly refused to repeal them. In doing so he gained enemies amongst rich and poor alike.

Perceval repeals the Elizabethan Statute of Artificers: 1812

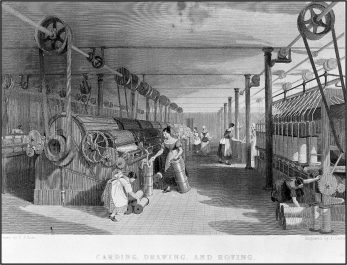

In 1812, after nine years of financing the Napoleonic Wars, the government needed to lessen the strain on the treasury of fighting the war. How could they bring down the the cost of armaments and uniforms? One way was to reduce the cost of the labour producing these items. The Prime Minister, Spencer Perceval, did this by abolishing the Elizabethan Statute of Artificers in 1812. This took protections away from the apprenticeship system, which had existed since Tudor times. The apprenticeship system ensured that artisan and skilled labour would be adequately compensated with regulated, liveable wages. A seven-year apprenticeship prevented an oversupply of skilled labour, and consequently, kept wages high for these men. However, the Industrial Revolution provided a mechanised alternative to the labour of these skilled men. War is often, ‘the father of progress’ and speeded up the impact of industrialisation. New machines were designed and manufactured, and factories were built to house them. The livelihoods of future Cato Street conspirators, William Davidson, John Brunt , and Robert Adams were threatened by this “progress.” These three men were skilled labourers. Davidson was a cabinet maker and Brunt and Adams were cordwainers–bootmakers for officers of the Royal Horse Guard. Both professions were threatened by the repeal of the apprenticeship system. A skilled cordwainer took at least seven years to learn his craft; a layman off the street could learn to operate a boot manufacturing machine in a few hours. As a cabinet maker, Davidson went eighteen months without a wage before he picked up Arthur Thistlewood’s call for change. Once wage regulation was taken away from the artisans, it became more cost effective to pay unskilled workers to operate mass production machines across industries. Perceval realised that by diluting labour through restrictions on the apprenticeship system he could ease the strain on the National debt.

Perceval’s Frame Breaking Act: 1812

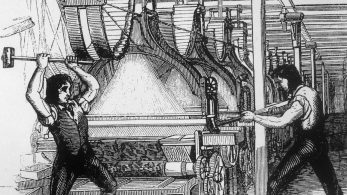

As with any major societal change, there were groups who fought back. The Luddites were a group that destroyed textile machinery in protest of the new technology. They took their name from Ned Ludd, a fictional figurehead who is rumoured to have broken two stocking frames in a fit of rage. They feared that these machines and mass-produced textiles would make their handicraft skills redundant and obsolete. Many members were traditional textile workers who had been forced out of work because of the new textile machines. After closing, these people could not find work in the new factories because it took fewer people to produce the same or greater amount of cloth on a machine. Out of work and growing in numbers and anger, the Luddites began attacking and sabotaging machinery in protest. The Luddites raided factories and destroyed stocking frames throughout Yorkshire and Nottinghamshire from 1811 to 1813. In 1812, Spencer Perceval pushed through The Frame Breaking Act , was passed by Spencer Perceval’s government. This made machine breaking illegal and a capital offence. Frame breakers now faced public execution. Many people were angry and desperate enough to do something drastic. Angry enough to assassinate a prime minister.

No Comments

Add a comment about this page